A vision for a climate-focused community biology lab in Berkeley, California

“If flowers heal us, shouldn’t we also try to heal flowers?”

“If flowers heal us, shouldn’t we also try to heal flowers?” asks Stephen Buchmann, PhD in the final paragraph of “The Reason for Flowers.” The question sparked a sense of urgency in me even greater than the often-heard climate alarmism. And after dwelling on it for six weeks, I have formed the following idea.

TL;DR: The time is right for a climate-focused community biology lab. Passionate, curiosity-driven scientists and enthusiasts outside of industry and academia have made meaningful contributions to rocketry, personal computing, astronomy, and many other scientific disciplines. The confluence of affordable lab space in the East Bay and abundant low-cost, open-source tools means we can experiment with novel ways to tackle food security, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and design sustainable fuels and materials.

Biological experimentation is more accessible than ever

This is a pivotal moment for the biological sciences. The cost of DNA sequencing and synthesis has rapidly decreased. At-home CRISPR kits allow anyone to edit the genome of E. coli and understand the underlying molecular biology behind the CRISPR/Cas9 genetic engineering tool—the same tool used in Casgevy, the first FDA-approved CRISPR/Cas9 therapy to treat patients with sickle cell disease. Open-source Raman spectrometers and spectral libraries can aid in the accessible chemical identification of unknown samples, and do-it-yourself $400 plate imagers can capture data on growth, reflectance, movement, or fluorescence while studying organisms or conducting diagnostic methods. Open-source versions of AlphaFold3 have made structure predictions of conventional ligands, nucleic acids, and proteins accessible to everyone. Similarly, thanks to customizable and cost-effective lab automation tools like the OT-2 robot, high-throughput experimentation is within reach for resource-constrained and even home labs. It’s a great time to explore and build with biology.

This raises the question, what could we discover and invent if given the space and community support to relentlessly follow our curiosities?

The power of open, scientific third spaces

Enthusiastic amateurs have made their mark on many scientific disciplines. From 1975 to 1986, a group of computer hobbyists and enthusiasts, including John Draper and Steve Wozniak, presented prototypes and discussed challenges and opportunities linked to personal computing. Known as the Homebrew Computer Club, engineers with advanced degrees and self-taught hackers came together to bring the power of computing to the masses. The gatherings were equal parts technical and aspirational. During the first meeting on March 15, 1975, the 32 participants had a brief dispute over whether to represent binary numbers using base-8 (octal) or base-16 (hexadecimal) systems. Shortly afterward, the group brainstormed the potential use cases of a personal computer. “Uses ranged from private secretary functions: text editing, mass storage, memory, etc., to control of house utilities: heating, alarms, sprinkler system, auto tune-up, cooking, etc., to games: all kinds, TV graphics, x - y plotting, making music, small robots and turtles, and other educational uses, to small business applications and neighborhood memory networks.” Fred Moore, one of the club organizers, was right when he predicted that “home computers will be used in unconventional ways—most of which, no one has thought of yet.”

At the heart of the Homebrew Computer club is the notion of a scientific third space—a diverse community of like-minded enthusiasts with access to the necessary tools and knowledge to experiment with complex, technical ideas. Unlike academia and industry, scientific third spaces aren’t influenced by market pressures, commonly held yet sometimes flawed beliefs, or the desire to publish in prestigious journals. Instead, the scrappiness of third spaces promotes first principles thinking and intellectual freedom fosters a willingness to try things that appear unrealistic or likely to fail. Issac Asimov, an American biochemist and science fiction writer, captures the essence of scientific third spaces in his 1959 essay on creativity:

There must be ease, relaxation, and a general sense of permissiveness. The world in general disapproves of creativity, and to be creative in public is particularly bad. Even to speculate in public is rather worrisome. The individuals must, therefore, have the feeling that the others won’t object.

For best purposes, there should be a feeling of informality. Joviality, the use of first names, joking, relaxed kidding are, I think, of the essence—not in themselves, but because they encourage a willingness to be involved in the folly of creativeness. For this purpose I think a meeting in someone’s home or over a dinner table at some restaurant is perhaps more useful than one in a conference room.

Probably more inhibiting than anything else is a feeling of responsibility. The great ideas of the ages have come from people who weren’t paid to have great ideas. The great ideas came as side issues. To feel guilty because one has not earned one’s salary because one has not had a great idea is the surest way, it seems to me, of making it certain that no great idea will come in the next time either.

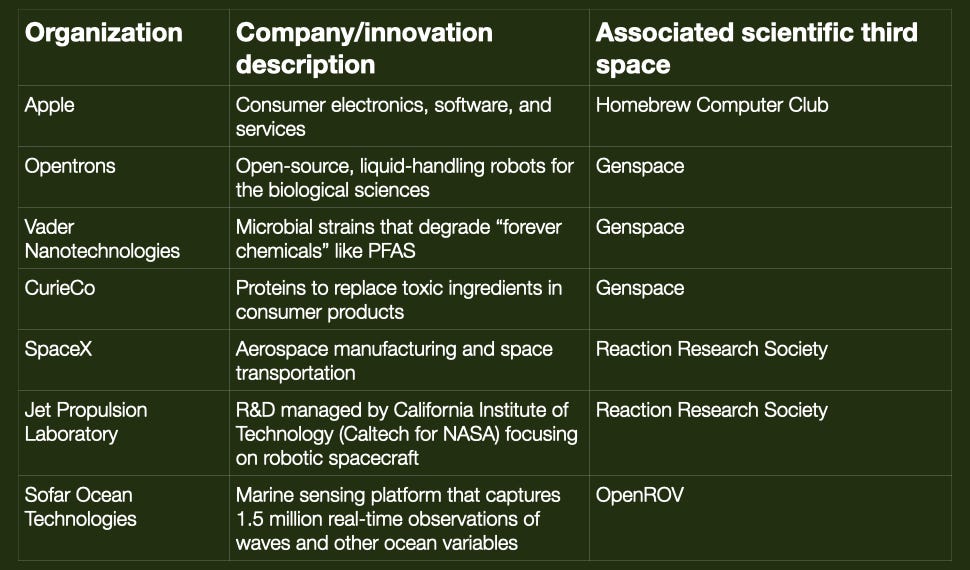

Tinkering, play, and ideation in a garage unintentionally led to the personal computing revolution, but this isn’t the only example of scientific advancement associated with informal, enthusiast efforts. Industries as far-flung as rocketry, astronomy, and the biological sciences have all benefited from scientific third spaces. Rocketry enthusiasts Tom Mueller and Hans Koenigsmann designed, built, and launched liquid-fueled rockets outside of Mojave, California, as members of the Reaction Research Society. They would later become early employees at SpaceX. Similarly, amateur astronomers discovered 42 planets in 2012 and spotted “yellow space balls”—a rare view of the early stages of massive star formation—by analyzing NASA images in 2015. The list goes on.

While scientific third spaces can lead to the creation of innovative companies, expecting that outcome is a mistake. The moment it’s assumed that tinkering will inevitably generate meaningful discoveries or incubate a startup, judgment is implicitly introduced into the community, stifling an atmosphere of play, learning, and exploration. However, the relentless pursuit of a shared goal cultivates camaraderie and accountability, strengthening the collective effort. Given our need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by half by 2030, a third space aimed at leveraging biology to tackle climate change could be deeply impactful.

Floral design—a gateway to exploring the technological potential of plants

Now, let’s return to the original question: If flowers heal us, shouldn’t we also try to heal flowers?

If the sentiment associated with flowers weren’t universally positive, the $30 billion cut flower industry simply wouldn’t exist. Yet, it does, owing to its prevalence in literature, art, and myth. In 1819, Le Langage des fleurs, a Parisian book detailing the meanings of single blooms and mixed bouquets, caused a splash in Europe by creating a way for lovers to communicate through flowers. Going back even further to the days of the pharaohs, we find that Egyptians were also lovers of flowers, using plants in perfumes, cosmetics, medicines, and more. If plant research could receive the same kind of universal acclaim bestowed on flowers, then we could reduce greenhouse gas emissions, ensure food security and even engineer new medicines.

Plants make up over 80% of global carbon (Gt C), and roughly 10% of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions comes from agriculture [1] [2]. To add salt to the wound, our food system is particularly vulnerable to climate change due to global warming, leaving us with the significant challenge of adapting our crops to changing environments. Simply put, subtle changes in growth conditions could impact whether you and I have food on our dinner tables. Despite the wide distribution and economic significance of plants, plant engineering lags a decade behind microbial and mammalian research [3].

Don’t get me wrong—there’s no doubt that the biggest agricultural companies, like Cargill, Monsanto (acquired by Bayer in 2018), and Syngenta, conduct in-house research. However, their responsibility to their shareholders and bottom-line makes the likelihood of investing in basic, high-risk research unlikely. And even if they decided to pursue underexplored research areas, their insights and data are likely kept behind closed doors.

Funders have recognized that plant-focused basic science and synthetic biology have lagged behind. In 2024, Homeworld Collective announced the winners of its Garden Grants—a total of $1.35 million in risk-tolerant funding for early-stage climate biotech ideas. Of the 16 funded projects, 5 focus on some aspect of plant engineering or have the potential to positively impact food security through agriculture. Similarly, ARIA recently announced its Programmable Plants programme, openly releasing its thesis on synthetic plants in order to receive feedback from the scientific community. Additionally, Fifty Years, a deep tech VC firm, launched its Manifest Climate Grants program to fund scientists leveraging biology to build the next climate solutions. Many additional funding opportunities exist and more continue to present themselves. Clearly there’s an appetite to address climate change and a recognition that leveraging plants is a promising way to do so.

Tackling climate change is just one of many avenues where the study of plants can lead to technological advancements. We could engineer plants so that they contain precisely-dosed medications that are currently given as injections. Imagine genetically engineering common food species that contain novel GLP-1 targeting peptides in their cell walls. Instead of receiving an Ozempic injection, you could take a daily pill with no prescription required. This isn’t science fiction—efforts like this are currently underway by the startup Evolv. In fact, you can already sign up for their waitlist on their website. To echo the words of Homebrew Computer Club’s Fred Moore, plant synthetic biology tools “will be used in unconventional ways—most of which, no one has thought of yet.”

Toward an open, climate-focused community biology lab

Since the launch of Jas and Olive on August 1st, many of you have expressed that you want to learn more about plant science. From breeding to tissue culture, many lessons from cut flower farming can deepen our understanding of the broader agriculture industry, and I intend to explore these topics on the blog, but you also brought up another desire—an urge to meaningfully and scientifically tackle climate change.

While powerful, plant biology is only one area of many that can be leveraged to combat climate change. Whether engineered or discovered, organisms can be used to extract metals from waste materials left after mining ore [4]. The optimization of carbonic anhydrase could lead to an energy- and cost-efficient way to remove CO2 from the atmosphere using aqueous solutions, and polyphosphate-mobilizing bacteria or optimized phytase enzymes that release phosphorus from phytate found in soil could replace phosphorus fertilizers [5] [6]. I’m sure it’s no surprise that I’m incredibly passionate about the potential of plants, but a climate-focused community biology lab could serve as a space where any climate-related endeavor could be explored.

Community biology labs aren’t new; they’ve existed for over 15 years. Genspace in Brooklyn, ChiTownBio in Chicago, and BioCurious in Santa Clara are a few of the established community labs in the U.S. Other efforts, like BIO4E (biology for everyone) led by Dr. Callie Chappell at Stanford, aim to create both a national community biology training program and more local, publicly accessible labs.* A climate-focused community biology lab would serve as a scientific third space centered on early-stage, curiosity-driven projects led by anyone. If we truly intend to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by half by 2030, we need all hands on deck.

Several key factors suggest that now is the time to open a climate-focused community biology lab, particularly in Berkeley, California:

There is an abundance of readily available lab space in the East Bay at reasonable prices. The recent downsizing, layoffs, and closures of many biotech companies have led to numerous sublease options (some for as little as $5,000/month) and plenty of talented, mission-aligned scientists seeking work.

A community biology lab with a climate focus will serve as a gathering space for mission-aligned collaborators who may otherwise find it difficult to experiment with one another. Scientists, entrepreneurs, designers, farmers, software engineers and anyone else who is enthusiastic about biology and tackling climate change can create and execute their own projects.

Floral design is a powerful introduction to plant molecular biology for the broader population. Many of you have expressed an interest in learning plant molecular biology. Because plant breeding, tissue culture, and synthetic biology protocols can be done by anyone, almost anywhere, it’s the perfect medium for those outside of the East Bay to contribute and participate. Not to mention that flower farming often relies heavily on fertilizer use, so designing more resilient and resource-efficient flowering plants could significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

For those who believe that meaningful work cannot be done outside of academia and industry, I encourage you to be more contrarian. Sebastian Cocioba, an amateur scientist based out of New York, has built his own home laboratory and supported projects ranging from engineering air-purifying houseplants to creating fragrant ones. Similarly, biology enthusiasts around the world are collaborating through the Open Insulin Foundation to develop organisms and protocols with the intention of creating an open-source model to produce insulin.

If efforts like these can thrive against all odds, imagine a world where we nurture and encourage amateur biologists. If that were possible, perhaps we’d successfully heal flowers.

Weigh in

Your feedback will help determine the feasibility of this vision so please chime in! I especially want to hear your opinion if you think a climate-focused community biology lab would fail. Based on financial modeling and your feedback, I’ll create and release either a summary of the bottlenecks prohibiting the opening of such a lab or a roadmap articulating next steps and requests for support.

Here are a few specific questions that I’m currently grappling with:

Inevitably, the scope of experiments would be limited by the available equipment in the lab. Certain efforts that require specific equipment, like the study of methanotrophs or anaerobes, likely aren’t a fit for a community biology lab. How do we determine the scope of projects that can be pursued? Is it useful to develop a thesis and articulate the specifics of certain problem areas as Speculative Technologies or ARIA have done, and then determine the lab needs accordingly? Or should the equipment aim to accommodate the broadest range of experiments?

What types of experiments or ideas would or wouldn’t be a fit for this lab? Why?

What problem areas have been published that could be leveraged to determine the scope of this lab?

What is the best way to quickly circulate results, whether successful or not, and ideas to maximize potential visibility and usefulness? BioRxiv? Substack? Another platform?

Are there enough scientists and enthusiasts in the East Bay who would want to be a part of a climate-focused community biology lab?

While community labs can extend experimental accessibility beyond academia and industry, they tend to pop up in dense cities with an established scientific presence. How do we increase experimental accessibility for those who don’t reside in these areas? Is this where cloud labs come in? Could a community biology lab serve as a cloud lab for others if equipped with Opentrons robots? Or should we aim to determine the minimal viable product (MVP) of a BSL1 lab? Other ideas?

This is by no means an exhaustive list of the things I’m considering at the moment. While I’d love to hear your responses to the questions posed above, I encourage you to express anything else that came to mind while reading this vision!

Acknowledgements

I also want to recognize a few people in particular for their time and encouragement to articulate the idea of a climate-focused community biology lab:

Xander Balwit: Critical feedback, Editing

Reilly Cooper: Critical feedback, Editing

David Lang: Brainstorming, Critical feedback

Elizabeth McDaniel: Critical feedback, Editing

Paul Reginato: Critical feedback

Harper Wood: Editing

*I’m a BIO4E Ambassador.

References

United States Environmental Protection Agency. (2024). Sources of Greenhouse Gas Emissions. https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/sources-greenhouse-gas-emissions

Bar-On YM, Phillips R, Milo R. (2017). The biomass distribution on Earth. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1711842115

Mccarty N. (2022). Plant Engineering Lags a Decade Behind: Index #62. https://www.asimov.press/p/plant-synbio-lags

Martínez-Bellange P, Bernath D, Navarro CA, Jerez CA. (2021). Biomining of metals: new challenges for the next 15 years. https://doi.org/10.1111/1751-7915.13985

Reginato P, McCormick C, Savitskaya J. (2023). Roadmap for biocatalysts in industrial CDR. https://doi.org/10.21428/23398f7c.482c898c

Scott BM, Koh K, Rix GD. (2024). Structural and functional profile of phytases across the domains of life. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crstbi.2024.100139

Jas what a great article! I was wondering how you’re thinking in terms of the business model? Would the lab be for-profit? How would it sustain itself? Also do you envision having any staff scientists? I didn’t see these questions in the end so I thought I’d add them here. Again, super exciting!

I’ve got some other ideas too! It would be amazing to work with plants in a community lab space but what about working with the bacteria that support plant growth? I think this would be something that could be explored more easily and quickly because bacteria grow faster and can be grown cheaply in a small space. My PhD was on rhizosphere bacteria so I’m particular fond of these little plant-growth promoters!